We expect computers to be perfect. We usually don’t give it a second thought. We expect the document opened today to look exactly the same as it did when it was saved last night. We expect the data inserted in a database to be returned when queried. That is unless somebody updated it in the interim in which case we’ll get back their data. We expect spreadsheet calculations to be correct. Do you ever go back and check the math? Of course not. Maybe your formulas but not the math. And most people implicitly trust the results returned by search engines. Do you ever look at the second page of answers? Only very rarely. Less than one percent of the time probably.

“That’s what the computer says” often ends the argument.

But I remember back in the 1970s, before the widespread adoption of electronic point of sale systems, when people would double-check the computer’s arithmetic because technical glitches would occasionally result in mistakes. Today, finding floating point arithmetic errors in Excel seems to be a little cottage industry. More often than not the problem occurs because precision wasn’t handled properly, but when the answer’s really not right it makes news, like the Excel 2007 bug that caused the results of certain calculations to be displayed incorrectly.

And now we’ve got all sorts of AI. So many wonderful tools with so much potential benefit: large language models, prediction engines, machine learning, and more. And so much potential damage: deepfakes, algorithm bias, manipulation, privacy concerns, and an epidemic of search result misinformation and suppression. I’ll talk more about ethics in a future article, but it’s best to heed the advice from Abraham Lincoln:

When we ask AI a question, should we believe the results?

Let’s look at that question a different way. What if instead you asked a friend. Would you believe their answer? Perhaps, but you would first consider their response relative to several factors. Is the question within their area of expertise? How reliable have they been in the past? How obscure is the information? Does the question require a precise answer, an explanation, or an opinion? And even then, they won’t always be correct.

The same applies to AI.

It’s important to understand the purpose for which an AI system was created, as well as the characteristics of the data on which it was trained.

It makes a big difference. Models will only be as accurate and unbiased as the data sets used to train them. I demonstrated the impact of training set error on model performance a couple weeks ago in …Unless You Want Accurate Results. Bias in media and technology sources is almost inescapable, and if those sources are used for an AI training set, that bias will be reflected in the model.

Furthermore, just like our friend, the AI won’t always be correct.

The goal of computers mimicking human intelligence, which is part of the definition of AI, is incompatible with perfection because human intelligence is not perfect.

Perfection in AI is an unrealistic expectation. As error is inevitable with human intelligence, it is similarly inevitable with AI. Customers will sometimes receive incorrect arrival time projections. Image recognition systems will sometimes misidentify animals and objects like chihuahua faces and blueberry muffins.

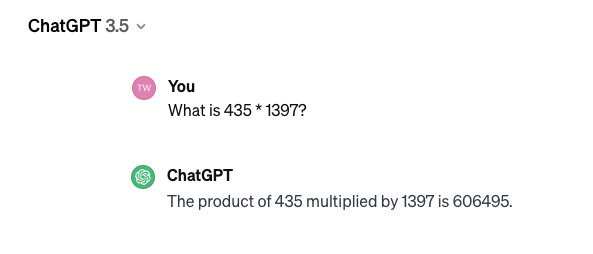

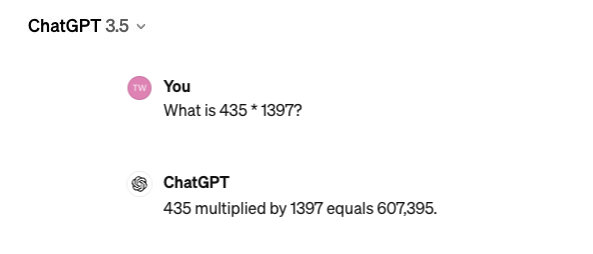

A couple months ago I ran a simple experiment. I asked ChatGPT to multiply a four-digit number by a three-digit number. It very confidently gave me the wrong answer.

The answer is actually 607695. I asked the same question again just now as I’m writing this and got a different, albeit closer wrong answer.

Interestingly, most of the individual digits were correct. If you read Neural Network (and ChatGPT) Magic Secrets Revealed you’ll understand why.

I have always believed that the primary barrier to the widespread corporate adoption of Artificial Intelligence is the fact that the answers will sometimes be wrong.

If companies are going to use Artificial Intelligence systems, then they must first get used to the idea that the answers won’t always be right. Many executives will have a hard time tolerating a system that they know will generate erroneous information. Of course, some errors are more consequential than others. That’s a judgment call they’ll have to make.

When asking a question to a generative AI system or even a search engine, you should know something about the answer you’re expecting. You need to be able to critically evaluate the results to determine whether they are at least reasonable (and preferably unbiased). This, of course, leaves you vulnerable to confirmation bias. In fact, your searches are analyzed so that the results presented are the ones that you most want to see. Data Skepticism definitely applies to AI and search.

AI is most effective when combined with human intelligence.

Ancestry.com has some of the best search algorithms, but of 1000 record hits, only a few may actually correspond to the person you’re researching. It’s easy to follow a false trail if you’re not careful and verify.

When the GPS gives you directions, it’s best to check them before you embark. The most “direct” route may take you zig-zagging through neighborhoods while the freeway will get you there faster.

The TSA has been introducing new facial recognition technology at airport checkpoints. Concerns persist due to privacy concerns, high rates of misidentification for non-white travelers, and reports of mistaken arrests as a result of misidentification. All this despite the fact that the system reports its result back to the agent at the podium who makes the final determination.

But, really, what is the agent going to do when “the computer says so”?

Finally, don’t ask generative AI to do math. In another experiment, I asked ChatGPT to solve a not very complex third-degree polynomial equation and it crashed and burned spectacularly. The answer it returned had multiple incorrect steps. The first and last were right, but just about everything in between was wrong. The point is to use the right tool for the right job. Use a calculator or a spreadsheet, or a platform built for solving equations like Wolfram Alpha (I have always loved Mathematica).

And use your own brain.

AI should augment human intelligence and other sources of information. AI is the assistant. Not the master.

The featured image for this post was AI generated using Canva.